[cmsms_row data_width=”boxed” data_color=”default” data_padding_top=”10″ data_padding_bottom=”10″][cmsms_column data_width=”1/1″][cmsms_divider width=”long” height=”2″ style=”dashed” position=”center” margin_top=”5″ margin_bottom=”5″ animation_delay=”0″][cmsms_text animation_delay=”0″]

New study provides strong evidence on dangers of excess weight

Being overweight or obese is associated with a higher risk of dying prematurely than being normal weight—and the risk increases with additional pounds, according to a large international collaborative study led by researchers at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the University of Cambridge, UK. The findings contradict recent reports that suggest a survival advantage to being overweight—the so-called “obesity paradox.”

The study was published online on July 13, 2016 in The Lancet (full text PDF).

The deleterious effects of excess body weight on chronic disease have been well documented. Recent studies suggesting otherwise have resulted in confusion among the public about what is a healthy weight. According to the authors of the new study, those prior studies had serious methodological limitations. One common problem is called reverse causation, in which a low body weight is the result of underlying or preclinical illness rather than the cause. Another problem is confounding by smoking because smokers tend to weigh less than nonsmokers but have much higher mortality rates.

“To obtain an unbiased relationship between BMI and mortality, it is essential to analyze individuals who never smoked and had no existing chronic diseases at the start of the study.”

— Frank Hu, professor of nutrition and epidemiology at Harvard Chan School

Hu stressed that doctors should continue to counsel patients regarding the deleterious effects of excess body weight, which include a higher risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

In order to provide more definitive evidence for the association of excess body weight with premature mortality, researchers joined forces in 2013 to establish the Global BMI Mortality Collaboration, which involves over 500 investigators from over 300 global institutions.

“This international collaboration represents the largest and most rigorous effort so far to resolve the controversy regarding BMI and mortality,” said Shilpa Bhupathiraju, research scientist in the Department of Nutrition at Harvard Chan School and co-lead author of the study.

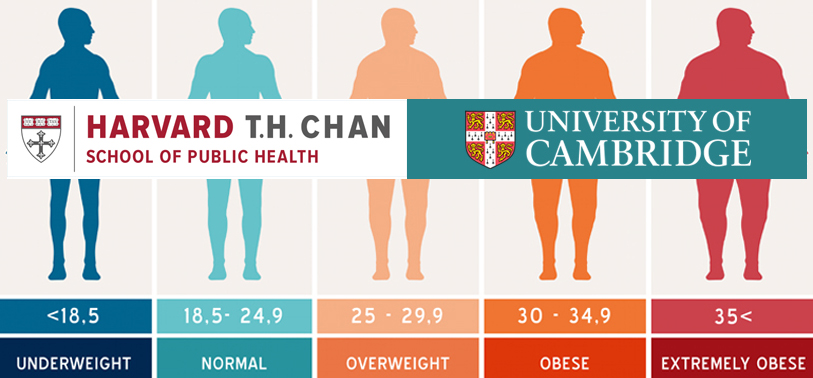

For the new study, consortium researchers looked at data from more than 10.6 million participants from 239 large studies, conducted between 1970 and 2015, in 32 countries. A combined 1.6 million deaths were recorded across these studies, in which participants were followed for an average of 14 years. For the primary analyses, to address potential biases caused by smoking and preexisting diseases, the researchers excluded participants who were current or former smokers, those who had chronic diseases at the beginning of the study, and any who died in the first five years of follow-up, so that the group they analyzed included 4 million adults. They looked at participants’ body mass index (BMI)—an indicator of body fat calculated by dividing a person’s weight in kilograms by their height in meters squared (kg/m2).

BMI is a simple index of weight-for-height that is commonly used to classify underweight, overweight and obesity in adults. It is defined as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters (kg/m2). In terms of kilograms and meters,

BMI = (weight / (height * height))

For example, an adult who weighs 70kg and whose height is 1.75m will have a BMI of 22.9.

BMI = 70 kg / (1.75 m2) = 70 / 3.06 = 22.9

In terms of pounds and inches,

BMI = (weight / (height * height)) * 703

[/cmsms_text][cmsms_table caption=”BMI Classification” animation_delay=”0″][cmsms_tr type=”header”][cmsms_td type=”header”]Underweight[/cmsms_td][cmsms_td type=”header” align=”center”]Normal Weight[/cmsms_td][cmsms_td type=”header” align=”center”]Overweight[/cmsms_td][cmsms_td type=”header” align=”center”]Obesity Grade 1[/cmsms_td][cmsms_td type=”header” align=”center”]Obesity Grade 2[/cmsms_td][cmsms_td type=”header” align=”center”]Obesity Grade 3[/cmsms_td][/cmsms_tr][cmsms_tr type=”footer”][cmsms_td]Less than 18.5[/cmsms_td][cmsms_td align=”center”]18.5 – 24.9[/cmsms_td][cmsms_td align=”center”]25.0 – 29.9[/cmsms_td][cmsms_td align=”center”]30.0 – 34.9[/cmsms_td][cmsms_td align=”center”]35.0 – 39.9[/cmsms_td][cmsms_td align=”center”]40.0 – 60.0[/cmsms_td][/cmsms_tr][/cmsms_table][cmsms_text animation_delay=”0″]

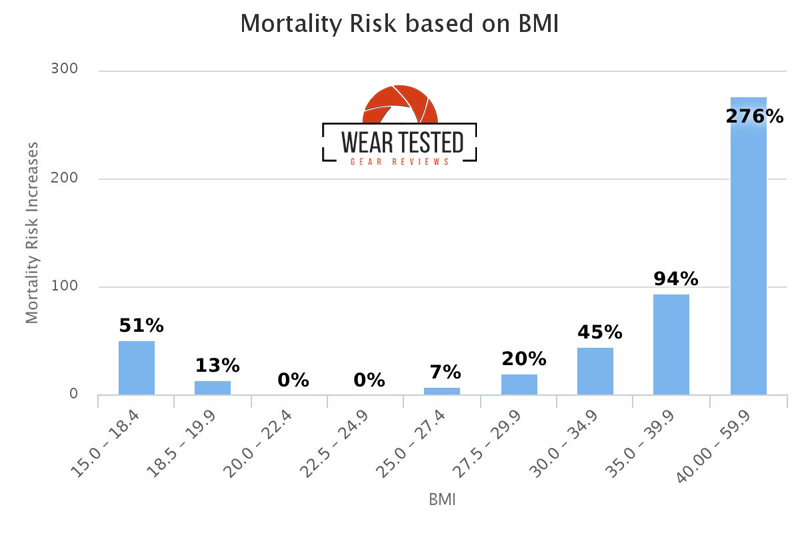

The results showed that participants with BMI of 22.5-24.9 kg/m2 had the lowest mortality risk during the time they were followed. The risk of mortality increased significantly throughout the overweight range: a BMI of 25-27.4 kg/m2 was associated with a 7% higher risk of mortality; a BMI of 27.5-29.9 kg/m2 was associated with a 20% higher risk; a BMI of 30.0-34.9 kg/m2 was associated with a 45% higher risk; a BMI of 35.0-39.9 kg/m2 was associated with a 94% higher risk; and a BMI of 40.0-59.9 kg/m2 was associated with a nearly three-fold risk. Every 5 units higher BMI above 25 kg/m2 was associated with about 31% higher risk of premature death. Participants who were underweight also had a higher mortality risk.

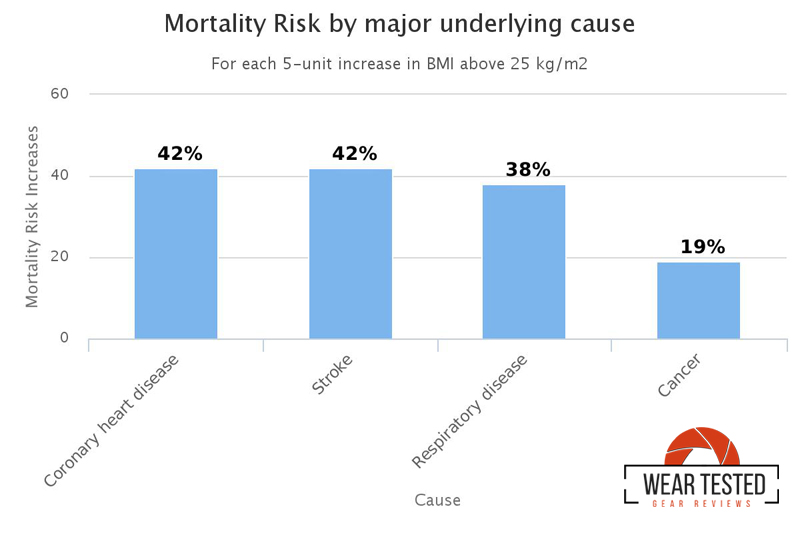

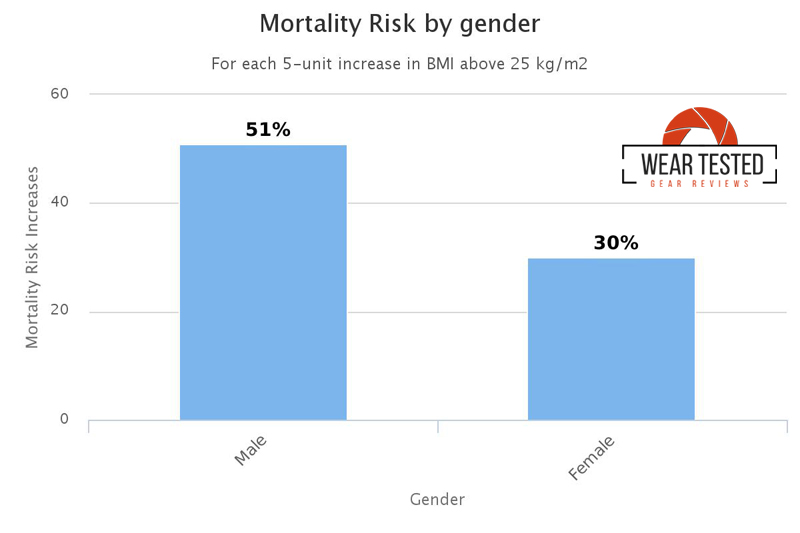

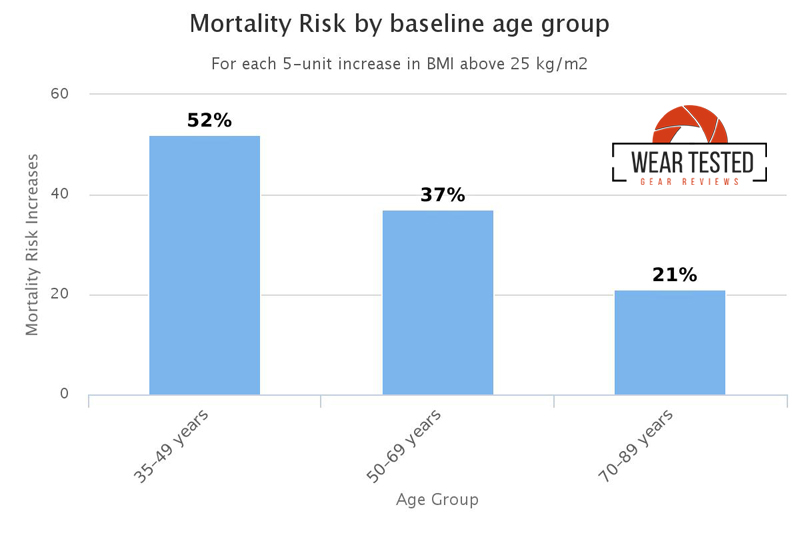

Looking at specific causes of death, the study found that, for each 5-unit increase in BMI above 25 kg/m2, the corresponding increases in risk were 49% for cardiovascular mortality, 38% for respiratory disease mortality, and 19% for cancer mortality. Researchers also found that the hazards of excess body weight were greater in younger than in older people and in men than in women.

Young obese males have the highest mortality risk, period.

[/cmsms_text][cmsms_divider width=”long” height=”2″ style=”dashed” position=”center” margin_top=”5″ margin_bottom=”5″ animation_delay=”0″][/cmsms_column][/cmsms_row]